The Early 2000s Memory Gap: Why Schools and Universities Need to Collect These Stories Now

Summary: The early 2000s represent a critical, and often overlooked, gap in many institutional archives. While this period marked the first wave of mass digital photography, fragile storage methods, obsolete technology and fragmented platforms have left many schools and universities with surprisingly little material from these years. This article explores why early 2000s memories are at risk, why now is the right time to collect them, and how schools and universities can run effective memory campaigns.

For many schools, colleges and universities, the early 2000s feel recent. Not quite “history”, not quite “modern day”. Somewhere in between.

And that’s exactly why so much from this period is at risk of being lost.

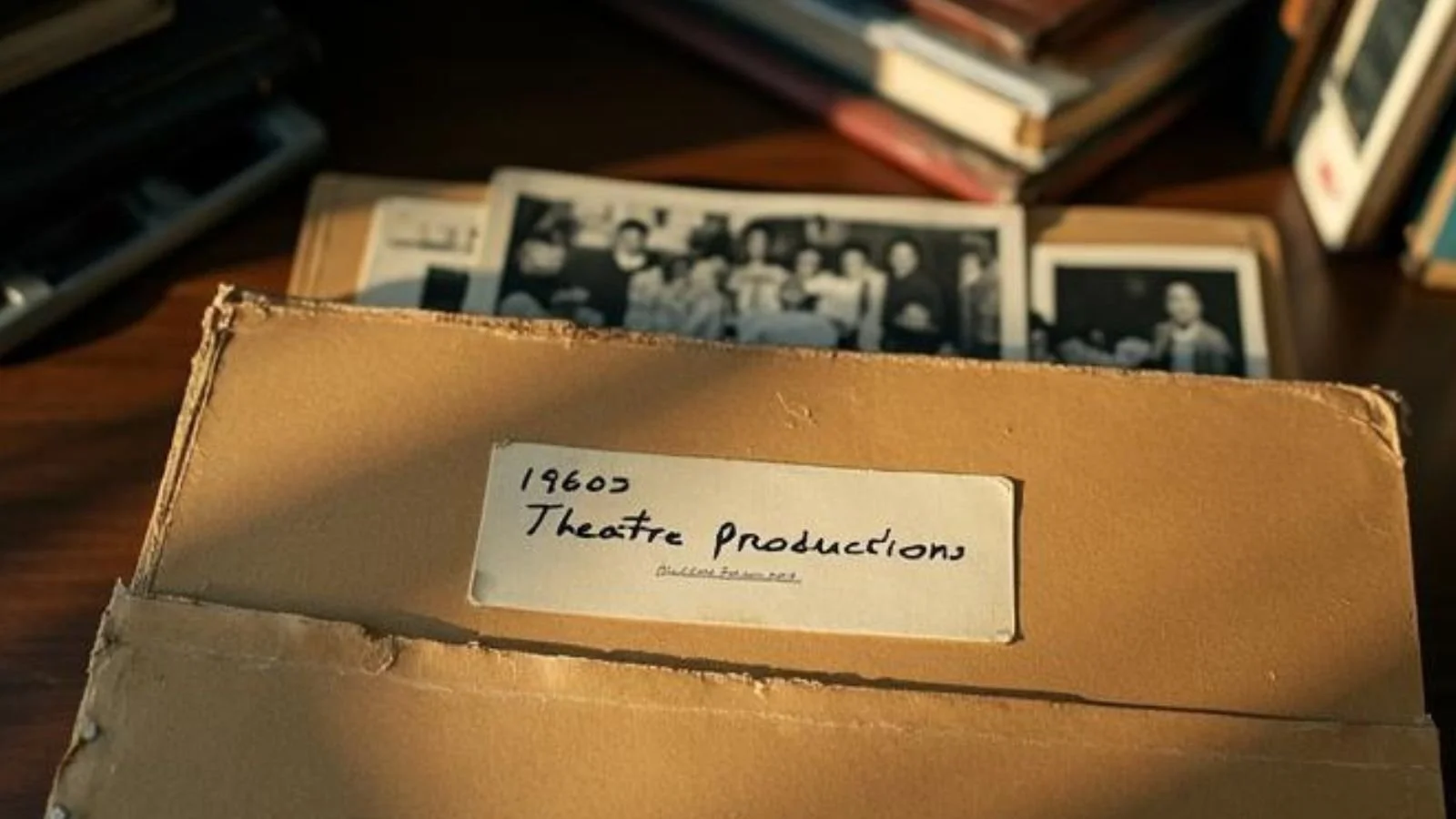

Across institutions, there’s a growing realisation that while archives often hold extensive collections from the 1950s, 60s or even earlier, the years roughly between 2000 and 2010 are strangely underrepresented. Photographs are patchy. Digital files are missing. Personal stories exist mostly in people’s heads and not in your archive.

This isn’t because nothing happened.

It’s because this period fell into a perfect storm of technological transition.

Why the Early 2000s Are at Risk of Being Forgotten

The early 2000s marked a turning point in everyday documentation. Digital cameras became affordable, photos became plentiful, and sharing images online became normal for the first time.

But while taking photos was easy, keeping them safe long-term was not.

There were no clear standards. No dependable cloud storage. No shared understanding of what digital preservation really meant. Images lived across personal devices and platforms that were never designed to last decades.

As a result, many institutions now find themselves with a strange imbalance: excellent historical coverage of earlier decades, followed by a noticeable dip at the very moment student life became most photographed.

The Forgotten Generation of Digital Memory

The early 2000s represent the first generation of mass digital memory, and one of the most vulnerable.

As this BBC article on why early 2000s digital photos are being lost highlights, an entire generation of images has quietly disappeared… scattered across broken laptops, obsolete devices and storage solutions that were never designed to last.

When Digital Abundance Met Fragile Storage

At the time, digital photography felt liberating. There were no limits on how many photos you could take. No film to develop. No immediate costs.

But abundance came with fragility.

Photos were stored on:

Personal laptops that were later replaced

CDs and DVDs that degraded or were misplaced

USB sticks with unclear labels

Memory cards that were reused

Early photo-sharing platforms that shut down or changed ownership

Email inboxes long since abandoned

It felt permanent. In reality, it was fragile.

Two decades on, many of those devices no longer work. Platforms have closed. File formats are obsolete. And crucially, institutions were rarely the custodians of this content. Individuals were.

The result is what many archivists and alumni teams are now discovering: a memory gap at the very point when student life became most visually documented.

Why this matters more than you might think

The consequences of this memory gap go beyond missing images.

Photographs don’t just document events… they capture culture, relationships, environments and everyday life. When they’re absent, so too is the nuance of how an institution evolved during a formative period.

A Generation at a Turning Point

The early 2000s cohort is now in its late 30s and early 40s. This generation is reaching a distinct life stage:

They’re moving houses or helping parents downsize

Helping parents clear attics and cupboards

Discovering boxes of printed photos they forgot existed

Finding old CDs, DVDs and USB drives with unclear labels

Reflecting on identity, belonging and legacy

This matters for institutions because this is often the last practical moment to capture these materials with context.

Once hardware fails or physical items are discarded, the opportunity disappears. But right now, many people still have:

Partial collections

Printed photos

Fragmented digital files

Clear memories of people, places and moments, even if the images themselves are gone

Which raises an important point:

Preservation isn’t just about photos

When institutions think about collecting the early 2000s, the focus is often on missing images. But memory is broader than photography alone.

If someone no longer has the photos, they may still be able to:

Record a short audio reflection

Share a video memory

Write about a formative experience

Describe people, traditions, spaces or events

Explain why certain moments mattered

These first-person narratives are often more powerful than images alone.

They add voice, emotion and meaning, and they help future audiences understand what student life felt like, not just what it looked like.

Why now is the right time to act

Institutions often assume they can “come back to this later”. But the early 2000s window is uniquely time-sensitive.

Memories are still vivid

People are emotionally reflective

Materials still exist in some form

Alumni are reachable and digitally comfortable

There is a growing interest in legacy and contribution

Wait another 10–15 years, and the challenge becomes far harder:

Fewer physical artefacts remain

Context is lost

Personal connections fade

Engagement becomes more difficult

In archival terms, this is a live collection opportunity, not a retrospective rescue mission. The longer it’s delayed, the more difficult it becomes.

What an early 2000s memory campaign can look like

One of the most effective ways to address this gap is through a targeted memory campaign.

Rather than asking for everything, successful campaigns:

Focus on a specific time period (e.g. 2000–2010)

Use clear prompts

Offer multiple ways to contribute

Make participation easy and meaningful

Simple prompts that encourage participation

For example:

“Do you have photos from your first year?”

“What do you remember most about student life in 2003?”

“Which places on campus meant the most to you?”

“What friendships or traditions defined your time here?”

Small contributions, collected at scale, build a powerful shared record.

How SocialArchive helps you capture and preserve these stories

SocialArchive is designed specifically to help institutions collect, protect and share memories at moments like this.

Using SocialArchive, you can:

Invite alumni to upload photos, videos and documents directly

Capture audio, video or written reflections through Spoken Stories

Moderate and curate submissions before publishing

Preserve original files securely

Add context through tags, dates, places and people

Build themed collections around time periods or campaigns

This means even if someone no longer has their photos, they can still contribute meaningfully ensuring their experience becomes part of the historical record.

Beyond preservation: engagement and belonging

Collecting early 2000s memories isn’t just an archival exercise. It’s an engagement opportunity.

When alumni are invited to share their stories:

They feel recognised

They reconnect emotionally

They see themselves as part of a continuing community

They engage on their own terms

For many institutions, these campaigns also align naturally with:

Community storytelling

Fundraising and legacy conversations

Not because memories are transactional but because belonging precedes giving.

Why memory comes before giving

Belonging is the foundation of long-term engagement. Memory-led initiatives naturally support alumni relationships, anniversary planning and, over time, legacy conversations, without making participation transactional.

A bridge between generations

Another often overlooked benefit is intergenerational value.

Early 2000s stories help:

Current students understand how student life has evolved

Younger alumni see continuity

Institutions document cultural and social change

Archives reflect lived experience, not just official narratives

This period captures:

The rise of digital culture

Shifts in communication and community

Changing student identities

Transitional educational experiences

Without deliberate collection, this chapter risks being underrepresented in institutional history.

Making this the year you safeguard the early 2000s

Every archive has gaps. That’s inevitable.

But the early 2000s gap is one we still have time to address if action is taken now.

Whether through photographs, audio reflections, short videos or written memories, institutions have an opportunity to capture a formative era before it slips out of reach.

This is not about recreating what’s already gone.

It’s about preserving what still exists.

With the right tools and the right invitation, those stories can still be saved.

Ultimately, tomorrow’s history depends on what we choose to collect today.

If you’d like to explore how SocialArchive can support an early 2000s memory campaign, or how Spoken Stories can help you capture voices even when photos are missing, we’d love to talk. Send us an email or book a demo to find out more.

Key Takeaways:

The early 2000s are a major blind spot in many institutional archives, despite being heavily photographed at the time.

Digital photos from this era were often stored on fragile, short-lived technologies that were never designed for long-term preservation.

Alumni from this period are now at a life stage where memories and materials are resurfacing, creating a time-sensitive opportunity to collect them.

Preservation isn’t just about images; audio, video and written memories can capture powerful context even when photos no longer exist.

Memory campaigns focused on a specific time period are an effective way to reconnect alumni and safeguard this chapter of institutional history.

FAQs:

Why are early 2000s photos more at risk than older photographs?

Unlike printed photos from earlier decades, early digital images were often stored on laptops, CDs, USB sticks or early online platforms that have since failed, degraded or disappeared. Many were never properly backed up.

What if alumni no longer have photos from this period?

Photos aren’t the only valuable form of memory. Audio recordings, video reflections and written stories can preserve experiences, relationships and culture, often adding depth that images alone can’t provide.

What is a memory campaign?

A memory campaign is a focused initiative inviting a specific group (such as early 2000s alumni) to contribute photos, stories or reflections around a shared time period or theme, using clear prompts and simple submission tools.

Why is now the right time to collect early 2000s memories?

Memories are still vivid, materials still exist in some form, and this generation is increasingly reflective. Waiting risks losing both context and content.

How does SocialArchive support this kind of project?

SocialArchive helps institutions crowdsource memories, preserve them securely, and share them in engaging ways. Alumni can contribute photos, videos and stories to one digital space, where content can be moderated, curated into collections, and reused to strengthen connection and engagement.